My journey to this book was a bit unusual. Though it’s been more than a decade now, I still have vivid memories of watching Dinotopia, a TV adaptation (featuring the incomparable David Thewlis) of a book by illustrator James Gurney. I rediscovered Gurney’s work about a year ago on a YouTube binge and was hooked immediately. Gurney is widely considered the world’s preeminent dinosaur artist, using fossils and discussions with scientists to produce lifelike portrayals of dinosaurs. Seeking more information about the animals depicted by Gurney (and to pull myself out of the YouTube sinkhole), I picked up this book by Steve Brusatte to continue my exploration of dinosaurs in a more scientific fashion.

Brusatte admits early on that the “rise” of the dinosaurs is difficult to pinpoint. The division between dinosaurs and their “dinosauromorph” predecessors is rather arbitrary, and new discoveries make the boundary even fuzzier. The book describes the early days of these creatures (~240 million years ago), which lived initially in the shadow of more dominant species like the crocodilian Saurosuchus and giant salamander Metoposaurus. By 200 million years ago, when volcanoes reforged the earth in the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, dinosaurs were able to exploit the deaths of their terrestrial competitors to assume a new role as the dominant land animals.

Brusatte acknowledges throughout the book that some chapters and sections are actually expanded adaptations of his articles from Scientific American or Nature, and the book as a whole feels as much. He spends significant time recounting archaeological expeditions and fossil discoveries, hopping somewhat randomly between geologic eras. While interesting, the result is sometimes stilted, a jumble of discussions and anecdotes resembling a long-form CV rather than a narrative examination of the rise and fall of Dinosauria.

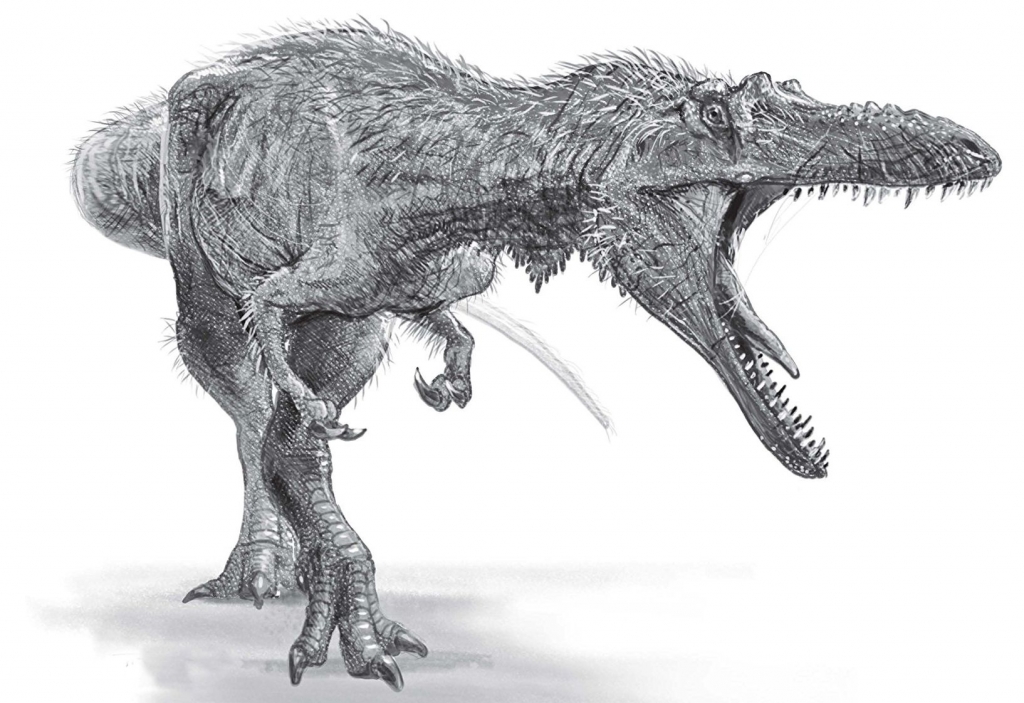

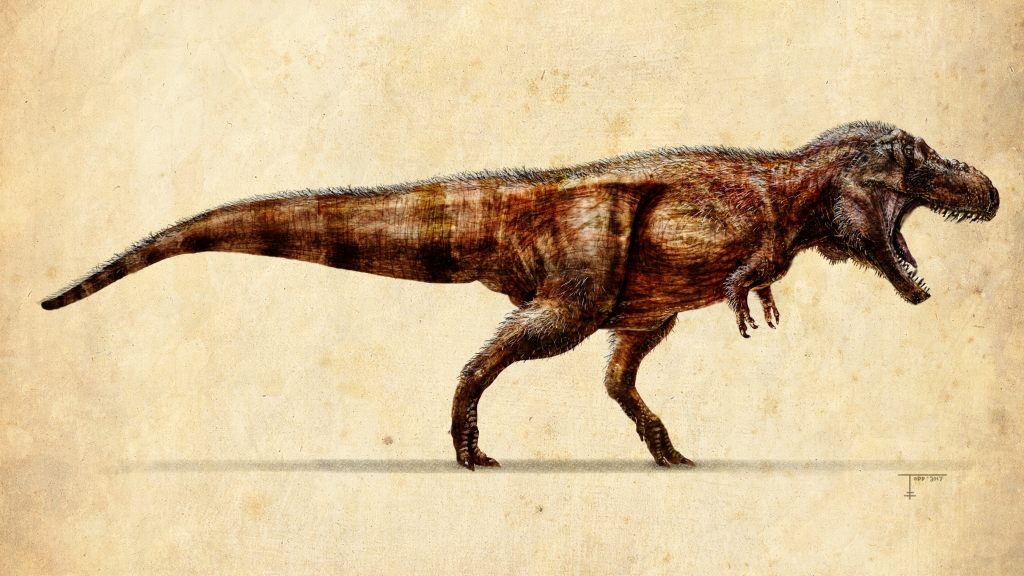

Despite this, some of the chapters themselves are fascinating. Brusatte is obsessed with Tyrannosaurs, dedicating an entire chapter to them and dispelling some irksome falsehoods. Rather than being dumb, solitary scavengers, the science increasingly suggests an intelligent, feathered T. rex that hunted in packs by ambushing its prey – more akin to the depiction of Velociraptors in Jurassic Park than to T. rex itself. Their arms, far from being useless, were muscular enough to hold prey hostage as Rex ripped them apart. I’m a big fan of this version of the King of Dinosaurs.

Illustrated by Todd Marshall

Where Brusatte excels most, though, is interpreting the archaeological finds and science of the Dinosaur Age into visceral and compelling descriptions of what life may have been like when these creatures walked the earth. These exceptional passages read almost like momentary glimpses through time machines, breaking up the discussion of fossil collections and field expeditions with interjections like this one, about the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago:

“Then the rains came. But what fell from the sky was not water. It was beads of glass and hot chunks of rock, each one scalding hot. The pea-size morsels pelted the surviving dinosaurs, gouging deep burns into their flesh. Many of them were gunned down, and their shredded corpses joined the earthquake victims on the battlefield.”

This final extinction event left the world in smoldering ruins, but it didn’t kill everything. We still have dinosaurs living among us: birds. All modern birds are descendants of the theropod line of dinosaurs and scientific discoveries continue to make that evolutionary line even more fantastic to behold. Within a week of finishing this book, archaeologists published the discovery of the world’s smallest dinosaur, resembling a toothy hummingbird. Even if Brusatte’s tale was stilted at points, it has opened my eyes to the fascinating world of archaeological research.

4/5: A bit disjointed, but worth it to read about a feathered T. rex in its most fearsome form