It has been more than half a century since the original publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962. While much has changed – agricultural technology now incorporates transgenic crop modifications, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been formed, and a wide variety of chemical pesticides and fertilizers have been banned in the US due to their established harms, to name just a few – the core substance of the book and Carson’s broader analysis and conclusions (oftentimes in the form of her warnings to future generations) are still relevant today. Humans, despite and often as a result of their wisdom, have a powerful effect on nature and global ecosystems. More often than not, that effect is negative and long-lasting. Rachel Carson establishes just how bad our impact as a species is, and what – if anything – we can do to reduce that impact while maintaining our quality of life.

Even in this central theme, which can be identified within the first chapter of the book, the reader can see terminology and thought processes that foreshadow the formalization of sustainable development later in the twentieth century. Although Carson wrote before the concept of sustainable development truly took hold either in the engineering world or in popular study (the Brundtland Commission established the most popular definition of sustainability in 1983), the various aspects of sustainability are intricately woven through Silent Spring’s narrative. Carson consistently addresses the three traditional pillars of sustainability (if not by their formalized names) and her analysis of each case study generally includes reference to the human and economic implications of potential policy changes, rather than simply addressing environmental concerns.

Her dedication to uncovering the inter-relationships of these different realms reveals the greatest strength of both Carson’s investigative style and Silent Spring as a work: the attention to complexity. Carson is an expert at revealing and analyzing the intricate web of natural inter-relationships that comprise various ecosystems and environments. The first half of the book is comprised almost entirely of chapters arranged in this extremely compelling style, using science, fieldwork, and copious evidence and case studies to illustrate the links amongst pesticide use, environmental status, and human quality of life. The chapters are arranged to become increasingly more emotionally compelling, beginning with descriptions of water and soil and climaxing with descriptions of plants, birds, and even all of humankind. In this way, Carson slowly and subtly transitions from a purely scientific analysis and almost environment-centric of the damages of pesticide use to an analysis (and argumentation) that is punctuated with intense emotional and political appeal.

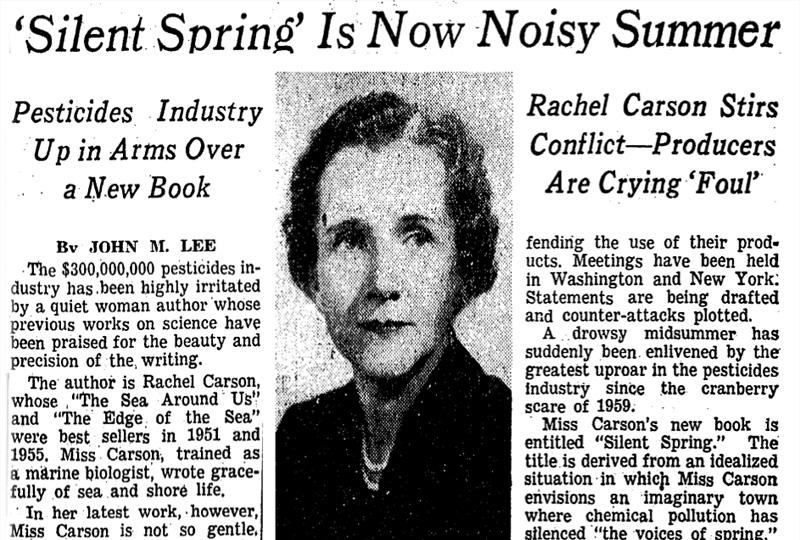

In this, Carson incorporates extensive familiarity with a second aspect of sustainability: human effects and influence. Carson is a scientist by profession and her publicity campaign for Silent Spring and subsequent testimony to Congress hinged on her depiction as a calm, rational scientist. Yet she is not ignorant of the human element – the negotiation that underpins political and cultural progress. Her arguments appeal to the sensibilities of the common American citizen and she frequently invokes the Bill of Rights and references the Founding Fathers to question what gives the government the authority to behave in certain ways. Here, she questions government aerial distribution of insecticides on private lands:

If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem. 1

Modern engineers could do much to learn from this approach. Carson’s narrative is never short of scientific analysis and she makes no point without appropriate evidence from lab- and fieldwork, yet she often supplements scientific argumentation with emotional and political appeals in an effort to drive her point home to a larger audience.

Carson does not neglect other aspects of sustainability either. Indeed, it is almost eerie to read Silent Spring after having read modern sustainability literature. So much of what is expected of engineers working in sustainable development today can be seen in a nascent form in Carson’s book. Silent Spring showcases the roots of lifecycle analysis in the context of pesticide production and distribution, especially highlighting the impacts of bioaccumulation of synthetic chemicals in populations of different organisms across generations of predator/prey relationships. Environmental economics concepts emerge in her analysis of economic internalization of the environmental impacts of pollution, and there is near-constant mention of environmental limits in the discussion of acceptable pollution levels in different organisms and ecosystems. And above all, Carson is committed to changing paradigms and standard practices within the scientific and agricultural communities.

Interestingly, given her commitment to changing accepted paradigms within American society, at no point in her book does she lambast the agricultural community or chemical companies as a whole. Rather, she willingly acknowledges at various points that reductions in the use of chemicals as a means of combating insects and disease must be considered in the context of the delicate balance that must be struck between society’s needs and the capacity of the environment to endure damage. Even in her criticism of the use of DDT – one of the book’s most powerful and enduring legacies – Carson approaches the problem from multiple angles, concluding with by avoiding a blanket condemnation of the chemical in favor of a stance that encourages spraying “as little as you possibly can.” 2

Silent Spring, despite its popularity, is not without its faults. In certain chapters more than others, and especially for modern readers, it reflects the era in which it was written and can feel quite dated. This is perhaps not unlike the way Origin of Species might feel dated to a modern reader; the two books are worth reading because they were revolutionary at the time and provide ground-breaking insight into controversial issues, but more modern texts might provide more updated and in-depth information. Silent Spring is notable for the impetus it gave to the environmental movement, yet simultaneously suffers because of this.

The book’s core theme is the deleterious effect humans and have had on nature in their attempts to control it, yet limits its examples to the realm of insecticides and pesticides. A more modern take on this theme would analyse human’s effect on the environment in other realms – particularly, perhaps, as consequences of industrialization. If it had been written ten years later, it surely would have analysed the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill (the largest spill in the US at that point) that was the direct progenitor of the US’s National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), which led the way in the creation of the EPA. 3 Beyond Silent Spring, a 1996 follow-up book by H. F. van Emden and David Peakall, helps address some of these gaps in issues and case studies that are the result of publication date, providing the reader with an additional 35 years of data and evidence. 4

Yet just as Carson lamented the rapid progression in the development and roll-out of new chemicals in the 1950s and 1960s, Beyond Silent Spring is increasingly out-of-date in its own analysis. The past twenty years have exhibited tremendous leaps in the development and distribution of transgenic crops and pesticides, the popularization of organic and vegan diets, and even “greenwashing” of some environmental ideas and concepts in an effort to increase popularity and sales (something that even Rachel Carson might not have predicted). There remains a tremendous amount of popular debate surrounding these issues and ideas, and Carson-esque examination of the inter-connected systems and communities would be a welcome addition to the current dialogue.

Despite these reservations, I agree with other critics in that Silent Spring is entirely worthy of the commendations it frequently receives. I recommend it to any engineer and budding environmentalist for two primary reasons. First, to study the ways in which Carson researched and analysed complex and intricate systems. Her treatment of the links among the various components in ecosystems and environmental “realms” verges on peerless within the community of scientific literature, and is especially impressive because it manages to blend scientific accuracy with uncompromising accessibility. Silent Spring was originally serialized for publication in The New Yorker, and much of its legacy stems from its approachability to readers not well-versed in scientific terminology or concepts. Carson appeals to this population without sacrificing her scientific integrity.

Second, readers should witness the narrative that drove the dawn and uptake of environmentalism. Silent Spring, while not the sole influence on the emergence of popular environmentalism, was a major factor in the US government’s revision of its environmental and agricultural policies. President John F. Kennedy was aware of the book’s wide-reaching impact, and Silent Spring was cited as a key influencer in the authoring of a wide variety of foundational environmental legislation. 5 While the fight against DDT has nearly reached the status of fable within the minds of today’s young engineers and other issues discussed in the book are similarly outdated, it is important to understand the difficulties faced by Rachel Carson and others and they endeavored to change systemic paradigms within American society. The challenges may be different in name today, but they may be fought and conquered in a similar manner.

Header Image: The Environment & Society Portal

NYT Headline Image: The Environment & Society Portal

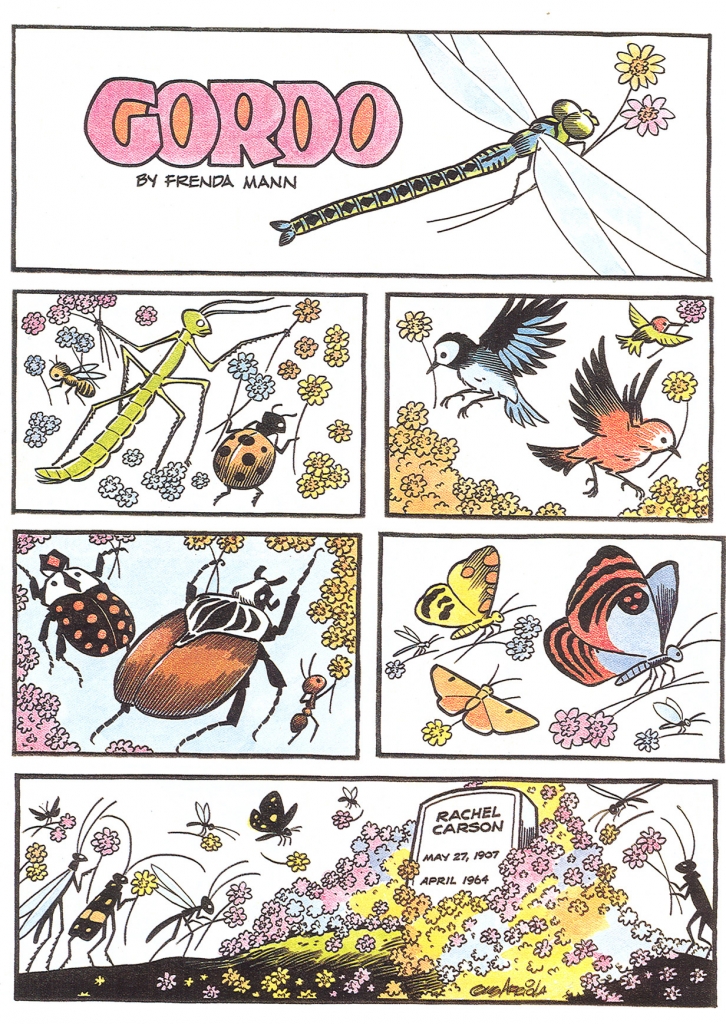

Justin Arriola Comic Strip: The Environment & Society Portal